Why Frank Lloyd Wright is still driving product design today

Like all great visionaries, Frank Lloyd Wright had the foresight to plan for the future. In 1955—just four years before his death at 89—he launched a licensing program that led to dozens of high-profile brand partnerships for decades to come. “Wright wanted to democratize design, and products were an approachable medium,” says Stuart Graff, president and CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. “He wanted to make thoughtful design a part of everyday life.”

Wright’s product designs play a pivotal role in his fabled portfolio. For his 1,114 architectural projects—of which 532 came to fruition—he designed thousands of furniture and decor items spanning dining room sets to office desks, textiles, vases and tablewares. “Many of his product designs weren’t properly cataloged [at the time], but when you look at the technical plans of past projects, they’re everywhere,” says Graff of the wide assortment of objects. In recent years, the foundation has turned its attention to Wright’s furnishings, both sketched and realized, to bring the late architect’s state-of-the-art works to a new generation of decorators. “Even 60 years after his death, his designs are still forward-thinking,” he says. “He put so many ideas into motion knowing they would be left in the hands of the future designers.”

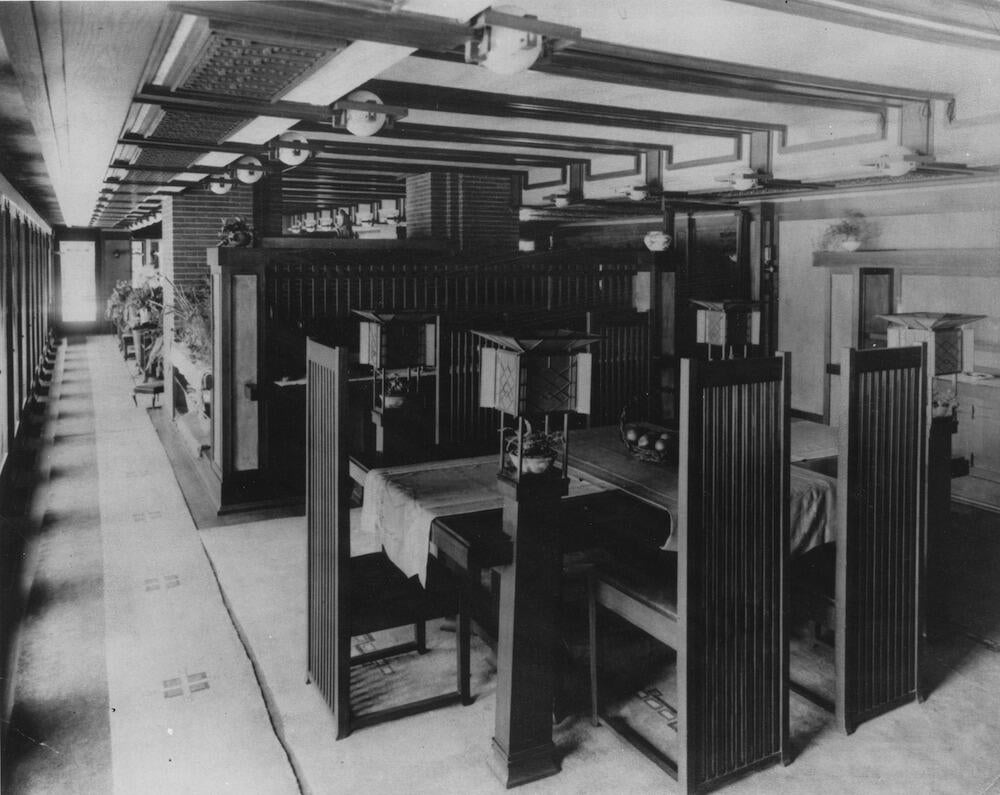

Of course, in order to fully appreciate the modern-day appeal of Wright’s designs, we must first understand his then-radical worldview. A proponent of the German philosophy of Gesamtkunstwerk—which roughly translates to “total work of art”—he fervently adhered to the belief that all artwork, whether paintings, operas or built environments, should be created as a complete, unified whole.

For Wright, this meant designing his spaces down to the dinner napkins—and in some cases, hostess gowns—so that his clients were truly immersed in his vision. “He approached all of his work with the goal of creating a deeper connection between man, nature and design,” explains Graff. “His products are an example of that synthesis in material form.”

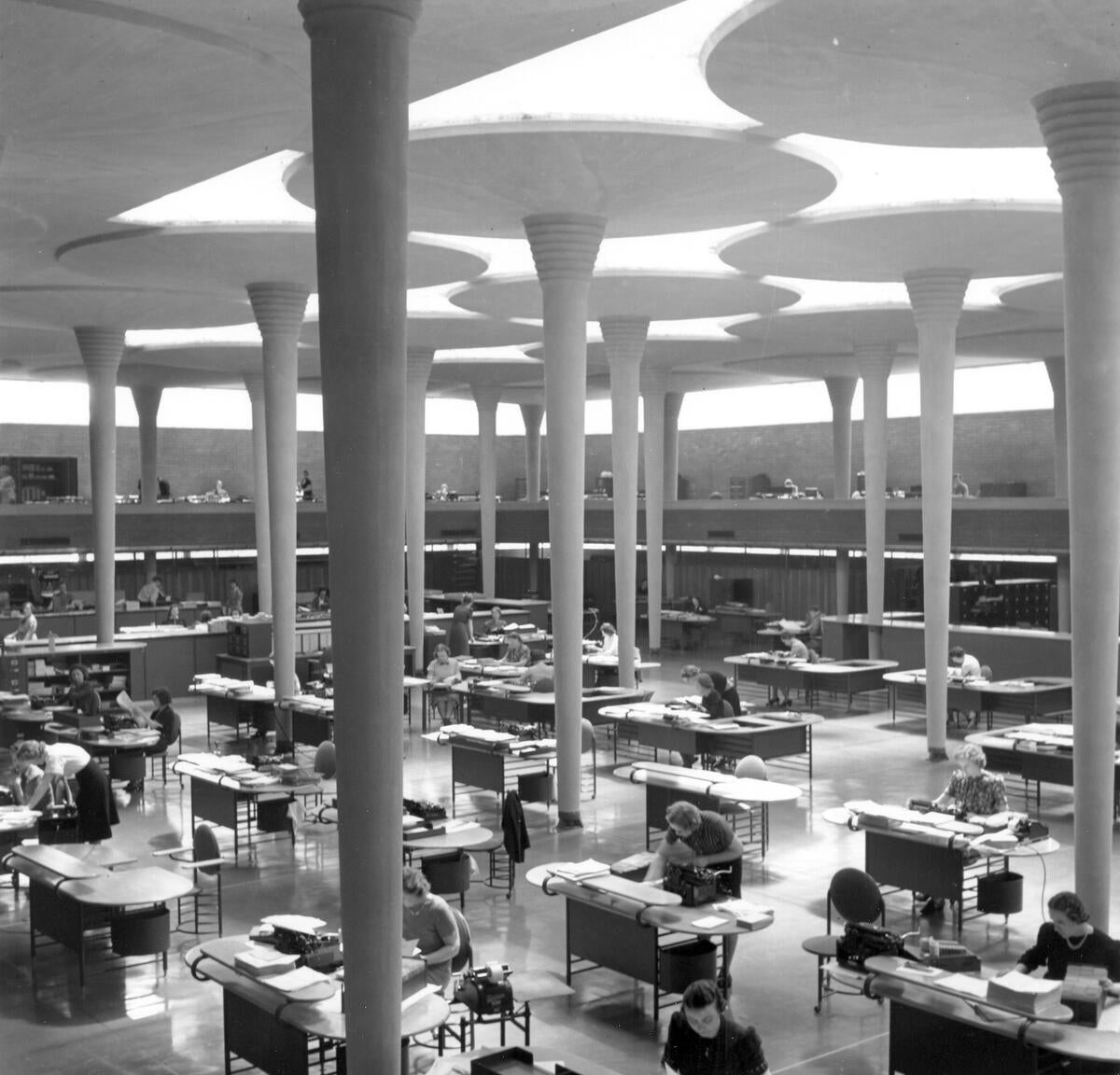

The iconic SC Johnson Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin, provides a superlative case in point. Completed in 1939 and widely considered to be Wright’s magnum opus, the building is buttressed by lily-pad-shaped columns that support its glass ceiling, and its open working space is outfitted with streamlined, ergonomic office furnishings including chairs with tilting backrests and multilevel desks with integrated filing cabinets and ample room for knee clearance.

In residential projects, meanwhile, he employed a symphony of cutting-edge client-focused designs ranging from wheelchair-accessible door knobs and light switches to insulating tall-back dining chairs and wall-mounted toilets for easy cleaning. “Despite [him] being so famously vain, Wright’s designs were extremely user-centric,” says Graff. “He wanted to elevate and improve his clients’ lives through design.”

By the early 1950s, Wright had developed a close friendship with legendary House Beautiful editor in chief Elizabeth Gordon, who frequently showcased his projects in the pages of the magazine. World War II had ended, stateside mass production was on the rise, and the political climate of the Cold War provided an opportunity to champion affordable American-made designs. “Wright’s whole ethos was casting off the Old World and building a new landscape based on American ideals,” says Graff. Wright’s licensing efforts were a key way to realize that vision: “This venture allowed him to make his designs available to everyone, not just paying clients.”

At Gordon’s insistence, Wright began licensing his products in 1955 to brands such as Schumacher (fabrics and wallpapers), Heritage-Henredon (furniture) and Martin-Senour Paints. However, these partnerships often proved problematic for Wright, who struggled to compromise on his unique vision for each design. “He signed deals and backed out of them, including one with Leerdam [glass],” says Graff. “He wasn’t just going to put his name on anything.”

After his death in 1959, the foundation continued to release licensed products with Schumacher until as recently as 2017, and launched numerous lines in collaboration with brands, including Tiffany & Co. (china, silver, crystal wares), Lego (toys) and Cassina, which reproduced Wright’s famed origami-esque Taliesin 1 armchair in 2018. “Over time, the program began to focus on a few of Wright’s best-known designs rather than the breadth and relevance of his entire portfolio,” says Graff. “We’re turning our attention to bringing a broader assortment of his designs to the market.”

Companies interested in reproducing or reinterpreting any of Wright’s domestic designs must first be vetted by the foundation’s licensing agency, Jewel, before they are granted access to the digitized archives for inspiration. Once a concept is agreed upon and a contract is signed, the foundation’s in-house design team collaborates with the brand’s designers on everything from preliminary drawings to prototypes until the final design is reached. “We don’t just put something out there that looks like Wright may have designed it,” says Graff. “It has to be grounded in his principles.”

Presently, more than 50 companies around the world hold licenses to develop Wright’s products. “His ideas are still some of the most interesting things happening in design today,” says Graff.

Take, for instance, Steelcase’s newly launched Frank Lloyd Wright Racine Collection. The collaboration features eight work-from-home-friendly designs from the architect’s aforementioned SC Johnson Administration Building project, whose furniture was originally manufactured by Steelcase more than eight decades ago. Three of the pieces, known as the Racine Signature line, are almost exact replicas, save for larger dimensions, while the remaining designs offer contemporary reinterpretations in expanded material palettes and colorways. “It’s in our brand’s DNA to offer user-centric furniture, so it was easy to apply Wright’s principles to updated designs,” says Meghan Dean, general manager of ancillary merchandising and partnerships at Steelcase. “The same beautiful yet utilitarian details that delighted users in 1939 still charm customers today.”

In 2021, Brizo unveiled the Frank Lloyd Wright Bath Collection. The collaboration took nearly four years from start to finish and offers 15 bathroom fixtures, including a showerhead, three different types of lavatory faucets, a tub filler, towel bars and a tissue holder. “As we designed, we asked ourselves what the bath space would look like through Frank Lloyd Wright’s eyes,” says Judd Lord, senior director of industrial design at Brizo. For the design team at Brizo, staying true to Wright’s vision meant looking to nature for inspiration. The Single-Handle faucet, for example, features a cantilevered spout that forges a side-flowing water stream meant to evoke a waterfall. The centerpiece of the series, the ceiling-mounted Raincan showerhead, boasts an integrated ambient lighting system that creates the illusion of a wall of sunlit windows. “For us, paying homage to Wright wasn’t just about his visual cues,” says Lord. “We truly wanted to understand and incorporate his underlying philosophy.”

In addition to furniture and fixtures, some licensing opportunities were centered exclusively on channeling Wright’s ethos into new categories. Crate & Barrel, for example, tapped Wisconsin-based brand Epicurean to create a collection of serving tools and cutting boards inspired by the graphic motifs the architect employed in his stained-glass windows. “Both the Crate & Barrel and Frank Lloyd Wright brands have a rich history in functional beauty and thoughtful design, as well as a deep consideration for the environment,” says Alicia Waters, executive vice president of Crate & Barrel. “This partnership was a natural fit.”

Looking ahead, Graff says the foundation is currently hard at work on a soon-to-be-launched line of fabrics with Designtex, as well as a living room collection by Steelcase. “Above all else, Wright believed that great design was based in nature and therefore timeless,” says Graff. “And like nature, great design is constantly evolving and finding new ways to meet the needs of the contemporary moment.”

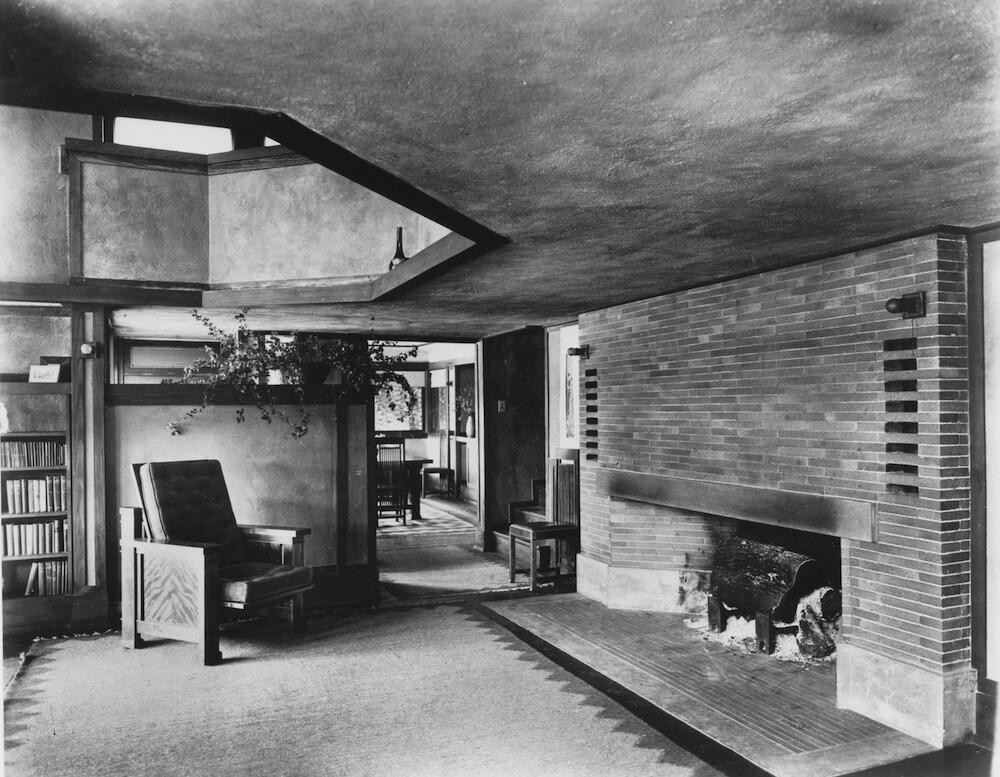

Homepage photo: An interior shot of the Isabel Roberts house by Wright, seen here in 1908 | Courtesy of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All Rights Reserved.